June 7, 2021

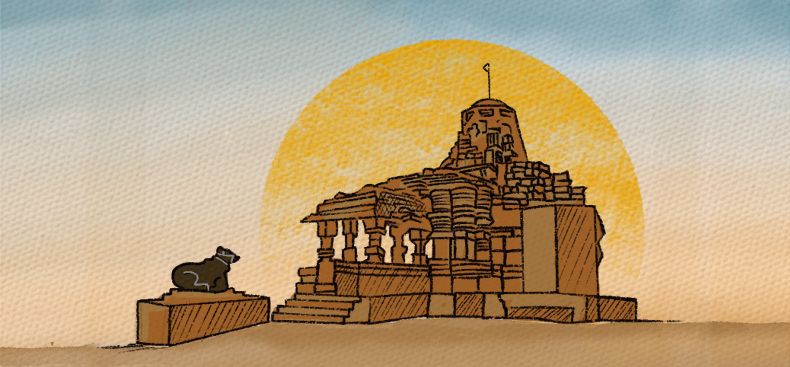

Not many people are aware that, between the fifth and thirteenth centuries, Śaivism—or Śiva Dharma—was the most dominant religious tradition within Hinduism. During this period, most of the Indian kings were Śaiva and patronized Śaiva institutions. For much of this time, Śaivism was also the dominant religion in most of south-east Asia, most notably in the Champa Kingdom of Vietnam and the Khmer Kingdom of Cambodia. Such was the dominance of Śaivism that even Mahāyana Buddhism modelled itself exclusively on the lines of Tantric/Agamic Śaivism, and transformed itself into a Tantric tradition called Vajrayāna. Jainism and Vaiṣṇavism also adopted and adapted Śaiva ritual techniques to their own tradition.

June 7, 2021

17 mins read

Not many people are aware that, between the fifth and thirteenth centuries, Śaivism—or Śiva Dharma—was the most dominant religious tradition within Hinduism. During this period, most of the Indian kings were Śaiva and patronized Śaiva institutions. For much of this time, Śaivism was also the dominant religion in most of south-east Asia, most notably in the Champa Kingdom of Vietnam and the Khmer Kingdom of Cambodia.

Do not neglect the truth. Do not neglect the Dharma. Do not neglect your health. Do not neglect your wealth. Do not neglect your private and public recitation of the Veda. Do not neglect the rites to gods and ancestors.

Treat your mother like a god. Treat your father like a god. Treat your teacher like a god. Treat your guests like gods.

– An ancient Hindu advice for a good life from Taittiriya Upanishad.