In the eternal playground of Krishna, bhakti is a drama and every emotion of a devotee is a rasa.

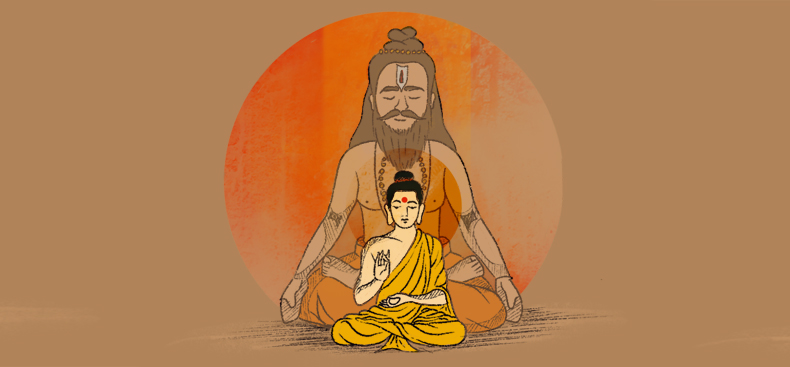

An Upanishad Teaching in a Pali Buddhist Text

Why should you love yourself the most? Yajnavalkya and Buddha have different answers.

6 mins read

April 5, 2021