Since the Upanishads conceive divinity as formless, eternal, and immaterial, the worship of divinity in a concrete form required theological justification. In the Vishnudharmottara Purana, the sage Mārkandeya says that the form of the whole universe is the vikṛiti or the modification of the Supreme himself. Worship and meditation are possible when the Supreme is endowed with form. Corporeal beings cannot easily apprehend the invisible state of the Supreme, therefore images are required to conceive, concretize and comprehend the Supreme. Similarly, another text probably from from the same period, the Vāstusūtra Upanishad, says that in the beginning, brahman was only a potentiality, without qualities (nirguṇa). This potentiality became manifest in the process of creation, and brahman appeared with qualities (saguṇa). Therefore, form is the precipitation of the creative impulse of the Supreme.

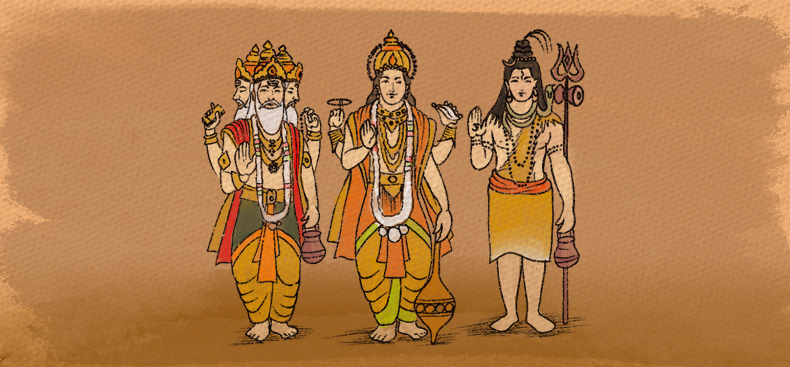

The Iconography of Lord Brahma

Vishnudharmottara Purana says that a learned image-maker should make Brahma four-faced, on a lotus seat, clad in black antelope skin, wearing matted hair, four-armed, seated on a chariot of seven swans. In the right hand should be the auspicious rosary and in the left the waterpot. The eye of that tranquil-looking image, wearing all ornaments closed in meditation, should resemble the end of the lotus petal. Vishnudharmottara Purana then gives the reason behind this symbolism.

Since Brahma is a creator God, his colour should be reddish, representing rajas or his creative activity. Creation involves the manifestation of space-time. Space is represented by the four arms of Brahma denoting four-cardinal direction – north, south, east and west. The Vedas, created at the dawn of the universe, is represented by the four faces of Brahma denoting the four Vedas – Ṛgveda the Eastern face, Yajurveda the Southern, Sāmaveda the Western and Atharvaveda the Northern. The rosary in Brahma’s hand represents the creation of time and its circular movement.

The worlds, both movable and immovable, have sprung from the primaeval water. Therefore Brahma holds these primaeval waters in a kāmandalu (water vessel) resting in his hand. The formless Brahma envisioned and projected the creation into existence through his meditative activity or tapas. Brahma, therefore, is always represented with eyes closed, sitting in a tranquil straight posture deep in meditation, visualizing the cosmos into existence.

The Iconography of Lord Shiva

According to Vishnudharmottara Purana, Shiva with five faces should be seated on a bull. On the crest of his matted locks should be the crescent moon, and his sacred thread should be Vāsuki, the serpent king. He should be represented with ten arms. In his right hands should be a rosary, a trident, an arrow, a staff and a lotus, and in his left hands should be a citron, a bow, a mirror, a waterpot and a skin. The colour of the whole (image) should resemble the rays of the moon.

Vishnudharmottara’s description of Shiva assumes that the reader is familiar with the symbolism behind Shiva’s iconography; therefore it skips over specific details. Usually, the five faces of Shiva represent the five elements: earth, water, fire, wind and ether. The snake Vāsuki that forms the sacred thread around his neck represents anger that destroys the three worlds, while the tiger skin represents desire (tṛṣna) for the world of senses. The two eyes of Shiva are the sun and moon, while his third eye is fire through which he destroys the world. This symbolism of sun, moon and fire will become very important in the subtle physiology of Haṭha yoga.

Shiva’s matted lock represents supreme brahman; the crescent moon on his forehead represents his divine powers (aiśvarya); the bull represents the four feet of dharma (in Hinduism, dharma is represented with four feet). The rosary and waterpot are emblematic of his ascetic nature. The citron (lemon) symbolizes the atoms that constitute the entirety of the universe (the idea that the universe is created out of atoms is very old in Hinduism). As is well known, the trident of Shiva represents the three qualities of prakṛiti: sattva, rajas, and tamas, together constituting the dynamic impulse of prakṛiti. In the Shaiva Tantra, the prakṛiti would be represented as the power of Shiva.

The Iconography of Lord Vishnu

Explaining the iconography of Vishnu, Vishnudharmottara Purana says that Vishnu should be depicted seated on Garuda, with his bosom shining with the kaustubha jewel, wearing all ornaments, resembling in colour the water-laden cloud and clothed in a blue and beautiful garment. Vishnu wears vanamāla (long garland of flowers), and in his right hands is an arrow, a rosary, a club and in his left hand is a skin, a garment, and a bow. This iconography, it seems, is peculiar to Vishnudharmottara. Usually, Vishnu has four hands carrying a mace, wheel, lotus and a conch.

Since this universe is a transformation of the Supreme, the colour of the transformation is black (kṛṣna). The creator and sustainer assume the colour black. The kaustubha jewel on his chest represents pure knowledge, and the thick garland of flowers (vanamāla) adorning his body represent the bondage of the world. Vishnu’s garments represent avidyā which supports the saṃsara. Using Sāṃkhya metaphysics, the mace and the wheel (chakra) at the hand of Vishnu represents the puruṣa and prakṛiti, the two uncreated primal cause of the universe. Further, Vishnudharmottara says that the mind as the evolute of puruṣa and prakṛiti permeates the entire creation, represented by Garuda, who can fly anywhere as quickly as the mind. The conch in the hand of Vishnu represents the sky and the waters, while the symbolism of lotus has multiple meaning in Hinduism, which we will cover in another essay.

Conclusion

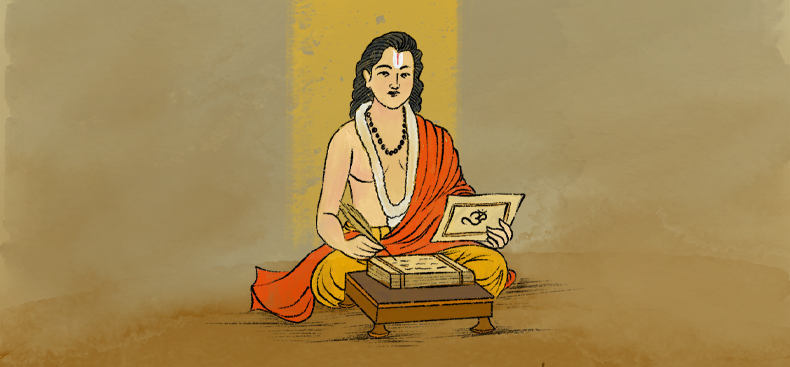

Vishnudharmottara then gives the iconography and its symbolism for other divinities: Agni, Varuṇa, Kuber, Narasiṃha, Hayagrīva, Sarasvati, Saṇkarṣṇa, Pradyumna, Vāsudeva, Krishna, Aniruddha, Tumburu, and many others. A worshipper who knows the symbolism and philosophy behind the iconography would be better equipped to meditate on his chosen form.

Vishnudharmottra Purana is a seminal text of Hindu art. It was the first time an independent compendium was written for music, painting, sculpture, architecture and dance. For the next 1200 years, Hindu tradition would produce very sophisticated texts and manuals covering all the known art forms. The increasing complexity of the textual tradition is reflected in the architecture and sculpture of the monumental temples built from the 8th century CE onwards, the sophistication of Hindu music and dance forms, and the aesthetic tradition of rasa.

(Note: For this essay, we have used Stella Kramrisch’s translation of Vishnudharmottara Purana. The critical edition and translation of Priyabala Shah can also be used.)